Synesthesia

Why some letters look red and others look blue.

What would a satisfying explanation for synesthesia look like? This explanation should be satisfying at all three levels of analysis: computational, algorithmic, and implementational. It should explain in a biologically plausible way how synesthesia develops and how it is experienced. Moreover, it should relate to our other theories of the brain and be hard-to-vary.

But what exactly is synesthesia? Synesthesia is the phenomenon where activation of one cognitive or sensory pathway leads to the involuntary activation of another. For example, grapheme-color synesthesia involves experiencing colors when you see letters, and sound-vision synesthesia involves experiencing colors when you hear certain pitches.

Synesthesia is typically one-directional, giving us a distinction between the inducer – the cognitive pathway that causes activation of another – and the concurrent – the pathway that gets activated.

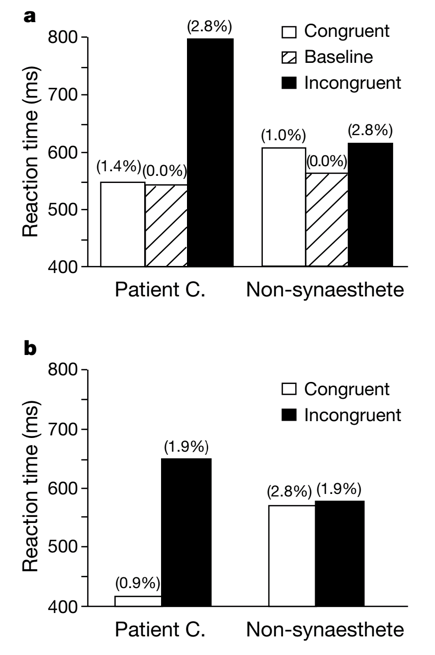

Evidence for synesthesia comes from both perceptual and neural studies. Since at least the 19th century, philosophers like Galton have documented reports of people experiencing synesthesia. More recently, many have corroborated these reports using psychophysical studies [1]. One common way people test for synesthesia is through a Stroop interference test. In a typical example of the Stroop effect, a person is presented with a word (say “green”) in a given text color, and asked to name the underlying text color. People are slower to identify the underlying color when it differs from that of the word, implying that the meaning of the color word somehow interferes with the identification of the text color.

Let’s say we have a synesthete who identifies “C” as appearing green. If their synesthesia is real, we should expect them to name the text color more slowly when it doesn’t match the synesthetic concurrent. Indeed, this is exactly what we observe in test like the following by Dixon and colleagues in 2000 [1]:

While the Stroop-test evidence is consistent with the experience of synesthesia, it might also be explained by associative learning, in which people associate certain letters with colors but don’t actively experience them. Further evidence, however, comes from neuroimaging studies. If color perception in synesthesia activated exactly the same areas as color perception, then it would become hard to argue that grapheme-color synesthetes do not perceive color with the inducer.

In 2005, Ramachandran and Hubbard reported that, when presented with certain letters, V4 – a brain area important for processing color vision – was more active in grapheme-color synesthetes than in non-synesthetes [2]. Heightened V4 activation is not the same as perceiving color, but this difference does support the explanation that grapheme-color synesthetes do have some visual experience of color and not just semantic associations.

So it seems likely that synesthesia exists. But how does it happen? To answer this question, we might start by understanding some of synesthesia’s properties. First, synesthesia is shockingly common. One 2006 review estimated the prevalence of synesthesia at 1.4% [3]. In addition, synesthesia appears to affect many aspects of cognition, with some studies, including one by Rothen and colleagues in 2012, finding that synesthetes demonstrate enhanced visual memory [4]. Moreover, synesthetes exhibits a kind of hypersensitivity to certain stimuli that also occurs in autism [5].

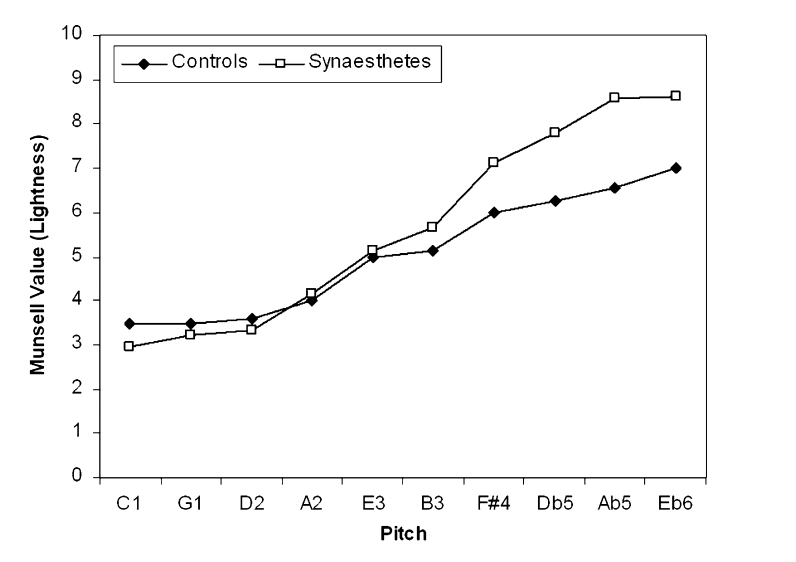

Synesthesia also shares features with non-synesthetic cross-modal perception. For example, when people are forced to choose lightness levels corresponding to certain pitches, non-synesthetes associate higher pitch with lighter colors the same way that synesthetes do [3]:

A few major theories have been proposed for the neural basis of synesthesia: these are disinhibited feedback, cross-wiring, and stochastic resonance. All are based in an overarching picture of the brain as a hierarchical prediction machine – lower-level sensory modules send feedforward signals to higher-level modules, which then send feedback signals to the sensory modules. Feedforward signals can be thought of as sensory input, while feedback signals can be thought of as predictions.

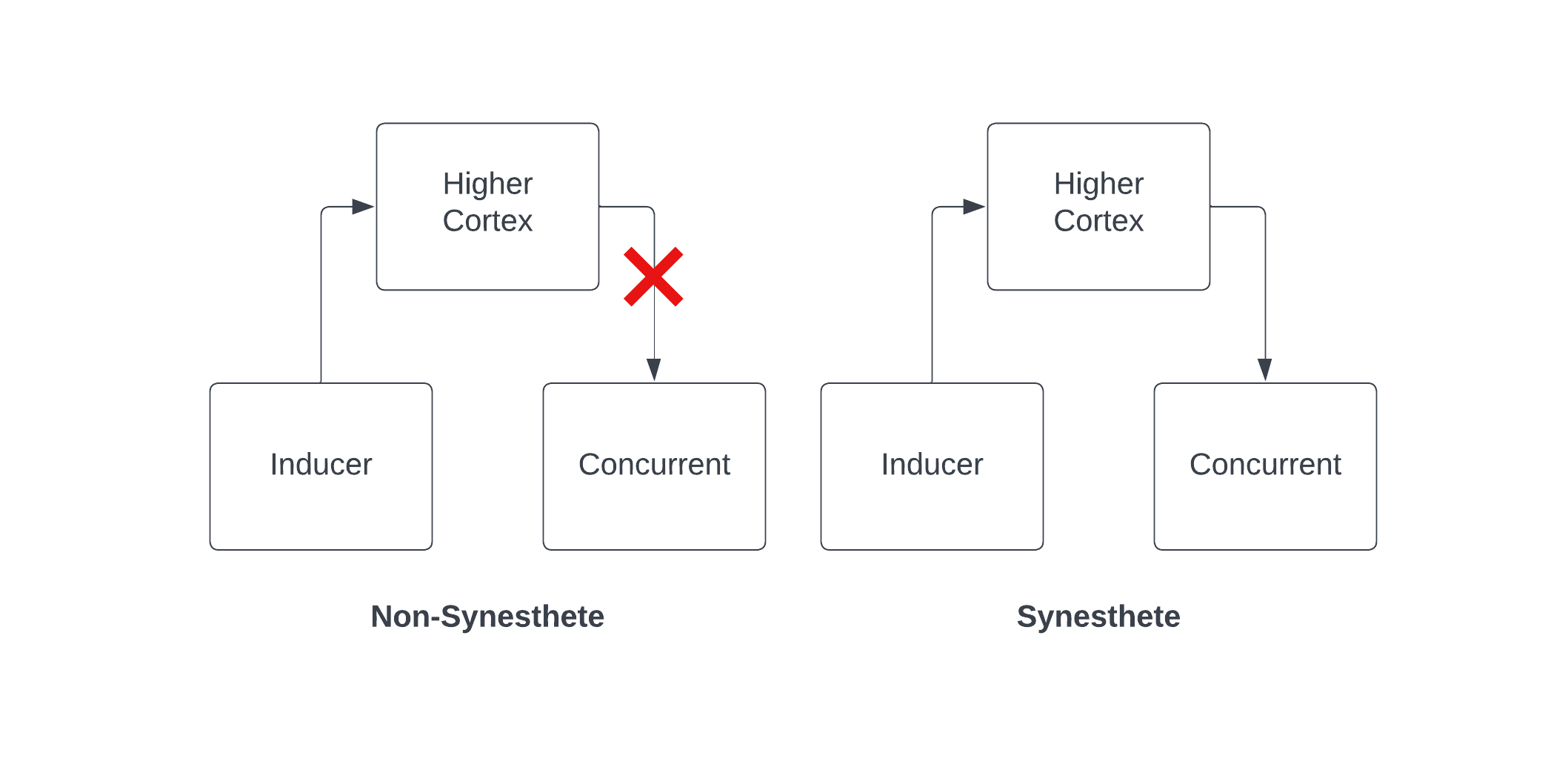

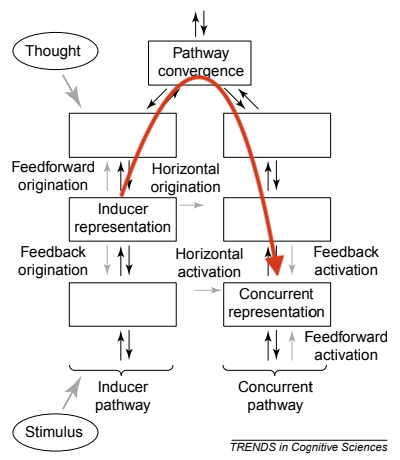

Disinhibited feedback proposes that synesthesia arises from disinhibited feedback signals from higher cortex to the concurrent. Schematically, this theory looks something like the following:

The theory of disinhibited feedback does a good job of explaining why synesthesia can be induced by drugs like LSD – after all, if it’s merely a difference in feedback signals, it’s not surprising that psychedelic drugs could lead to disinhibited feedback. It also helps explain why inducer representations are typically higher-level, learned concepts like letters and numbers, whereas concurrents are lower-level experiences like colors and spatial locations. If you additionally assume that mental imagery corresponds to top-down signals, this explains why the experience of synesthesia might feel more like mental imagery than perception [6].

In the following figure from Grossenbacher and Lovelace, disinhibited feedback would represent a path upwards from the inducer representation, through the pathway convergence, and down to the concurrent representation (as I have outlined in red).

However, disinhibited feedback fails to explain how synesthetic brains can differ in connectivity from non-synesthetic brains [7]. It also fails to explain why some synesthetes experience the concurrent as “out there” in the environment, rather than as mental imagery.

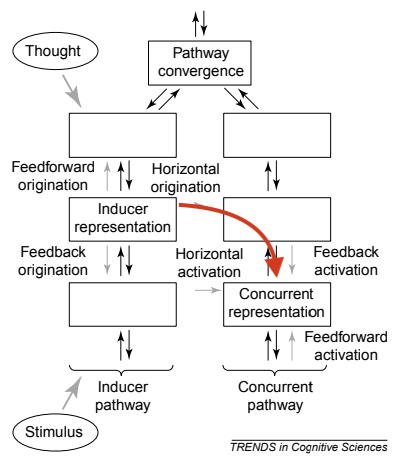

Looking closely at the diagram above might lead us to come up with an alternate explanation. Why not take the horizontal connections straight from the inducer to the concurrent?

Indeed, this is the cross-wiring theory of synesthesia, which proposes that synesthesia arises from increased feedforward connections between adjacent brain regions, going from the inducer to the concurrent [7]. This theory explains the two points that couldn’t be explained by the disinhibited feedback theory – synesthetic brains are more connected because that is exactly what constitutes synesthesia, and feedforward connections explain why some synesthetes report the concurrents as occurring “out there.” However, the cross-wiring theory fails to explain why synesthesia can induced pharmacologically or by visual deprivation. Although proponents of this theory might argue that induced synesthesia is “not real synesthesia” because the concurrents are not consistent, the theory does not explain why we should add the qualifier of consistency to our definition of synesthesia.

These two theories can be understood as follows, based on the kind of connection they involve (bottom-up or top-down) and whether they predict differences in brain structure or merely in function:

| Bottom-up | Top-down | |

|---|---|---|

| Structural | Cross-wiring (feedforward) | ? |

| Functional | ? | Disinhibited feedback |

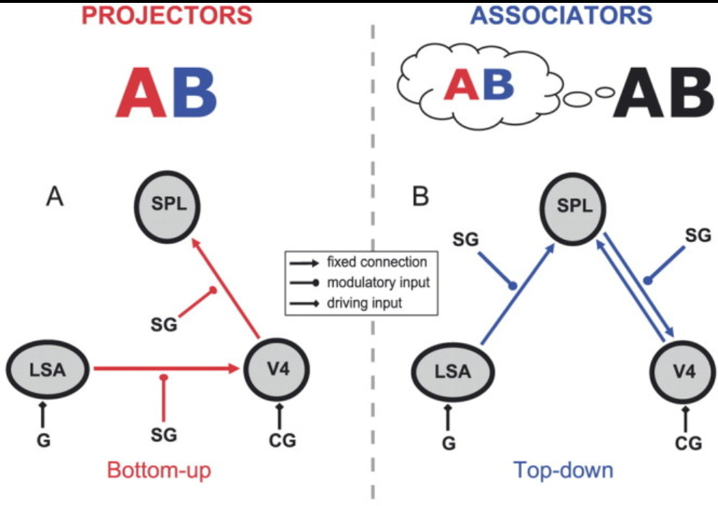

Upon examining the evidence, it appears that the difference between bottom-up and top-down theories of synesthesia might be resolvable, by observing that there are two kinds of synesthetes: associators, who make up the majority and experience concurrents as if they are mental imagery, and projectors, who perceive the concurrents as being “out there” in the environment. If such a distinction exists, we would expect to see different explanations for the two types of synesthetes. This is exactly what van Leeuwen and colleagues found in their study of projector and associator synesthetes. Using dynamic causal modeling, they found that projectors exhibited a bottom-up pattern of activation while associators exhibited a top-down pattern of activation. In the following figure, LSA refers to letter shape area, SPL refers to superior parietal lobule, and V4 refers to the aforementioned part of the visual cortex important for color perception.

Even though the top-down and bottom-up distinction might be reconciled by appealing to different kinds of synesthesia, and even if we elaborated the theories to fill in the question marks from the table (supplying a top-down and structural theory, as well as a bottom-up and functional theory) we would be left with a couple explanatory gaps. Why does synesthesia sometimes reflect differences in connectivity and sometimes differences in function? More importantly, why does developmental synesthesia correlate with additional conditions – such as hyper-sensitivity and enhanced visual memory – that don’t directly relate to the inducer-concurrent connection?

These questions, and more, can be explained by a third option: the stochastic resonance theory of synesthesia [9]. Stochastic resonance is a general principle of nature in which adding noise to a signal can facilitate its detection. In the stochastic resonance theory of synesthesia (SRS), synesthesia is explained by increased neural noise in the concurrent part of the cortex. In a way, it unites the theories of cross-wiring and disinhibited feedback, by explaining them both as consequences of neural noise levels.

Stochastic resonance explains how synesthesia can be induced – for example, if psychedelics enhance the neural noise in the visual cortex – how synesthesia can lead to differences in connectivity – via the reinforcement of existing cross-modal pathways – and how synesthetic associations seem to start uncertain in childhood and cement over time. It also explains the relationship of synesthesia to autism – as both involve high neural noise in the target cortex – and the way that genetically related individuals, when they have different forms of synesthesia, share a concurrent more often than they share an inducer.

What the stochastic resonance theory does is unify the functional and structural interpretations of synesthesia, by arguing that both stem from the same underlying cause: increased noise in the concurrent cortex. It suggests that synesthesia can be predicted by measuring levels of noise in the cortex. However, it has little to say about top-down and bottom-up processing – explaining these differences entails explaining the experience of synesthesia [9].

In a way, then, our present theories for synesthesia can be understood through two related problems. First, there is the question of how synesthesia develops, and this is where stochastic resonance theory provides an answer. Then, there is the question of how synesthesia is experienced. Such a theory would have to explain why synesthesia feels different from perception, and why different kinds of synesthesia feel different.

For now, the most compelling framework explaining the experience of synesthesia is predictive coding. This is a theory of the brain in which sensory modules provide feedforward inputs of “evidence” while high-level modules provide feedback inputs of “predictions,” and where these predictions modulate the evidence signals so that only the surprising evidence bubbles to the top. In this framework, no experiences are entirely top-down or entirely bottom-up, but the quantity and reliability of bottom-up evidence determine the experience’s degree of “perceptual presence” — that is, the sense that something is out in the real world. To quantify this, Anil Seth argues that experiences have “perceptual presence” when they are counterfactually rich – that is, they contain the information needed to make alternative predictions about the object [10]. In other words, the degree to which something feels real depends on the degree to which we can act upon it, not just in synesthesia but in any kind of perceptual experience.

Our understanding of synesthesia is not complete. Even precluding falsifying evidence for our existing theories, we lack explanations for the genetic basis of synesthesia – as it seems to be somewhat but not perfectly heritable – as well as what determines baseline levels of noise in the brain. What we do know about synesthesia supports the idea that the brain is a hierarchical prediction machine that uses cross-modal connections at several levels to modulate its predictions. Stochastic resonance theory helps explain the development of synesthesia, and predictive coding explains its experience. The task ahead is to identify the factors that modulate this modulation.

References

[1] Dixon, M. J., et al. (2000). Five plus two equals yellow. Nature, 406, 365.

[2] Hubbard, E. M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2005). Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia. Neuron, 48, 509-520.

[3] Sagiv, N., & Ward, J. (2006). Cross-modal interactions: Lessons from synaesthesia. Progress in Brain Research, 155, 263-275.

[4] Rothen, N., Meier, B., & Ward, J. (2012). Enhanced memory ability: Insights from synaesthesia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(8), 1952-1963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.05.004

[5] Ward, J., Hoadley, C., Hughes, J. et al. Atypical sensory sensitivity as a shared feature between synaesthesia and autism. Sci Rep 7, 41155 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41155

[6] Grossenbacher, P. G., & Lovelace, C. T. (2001). Mechanisms of synesthesia: Cognitive and physiological constraints. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5, 36-41.

[7] Bargary, G., & Mitchell, K. J. (2008). Synesthesia and cortical connectivity. Trends in Neurosciences, 31, 335-342.

[8] van Leeuwen, T. M., den Ouden, H. E., & Hagoort, P. (2011). Effective connectivity determines the nature of subjective experience in grapheme-color synesthesia. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 31(27), 9879–9884. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0569-11.2011

[9] Lalwani, P., & Brang, D. (2019). Stochastic resonance model of synaesthesia. *Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 374 (1770), 20190029. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0029

[10] Seth A. K. (2014). A predictive processing theory of sensorimotor contingencies: Explaining the puzzle of perceptual presence and its absence in synesthesia. Cognitive neuroscience, 5(2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2013.877880